Curator's Note

“A compelling urge toward new social opportunities is being clandestinely exploited in the interests of a property-owning minority.”[1] Written in the mid-1930s about the capitalist appropriation of film, Walter Benjamin’s statement holds no less true of contemporary developments in our increasingly “post-cinematic” environment. Much as Benjamin observed the obstruction of cinema’s revolutionary potential in a period of proletarianization and political upheaval, we can witness Big Tech’s consolidation of power during a global pandemic, marking what Naomi Klein has called the “screen new deal.” As profit-driven tech giants leverage the coronavirus crisis for a swift and permanent transformation of civic life, it is worth returning to Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” examining the possibilities and structural constraints that informed his theory of media.

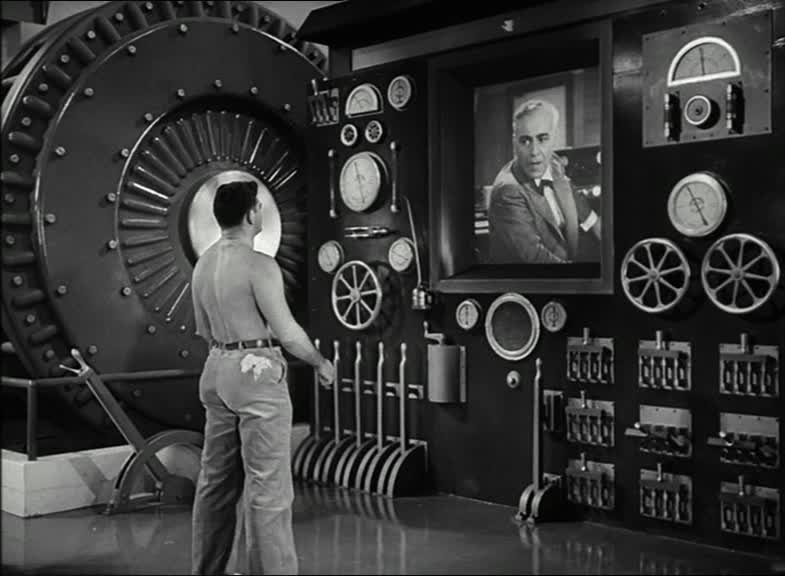

Benjamin addressed the aesthetic and social significance of cinema within a rapidly changing technological landscape. A medium of uncanny estrangement—one that reproduces actors in the form of detachable and transportable moving images—film offered working masses the opportunity to recognize their own dehumanizing self-alienation in the face of a “vast apparatus whose role in their lives is expanding almost daily.”[2] In the productions of Charlie Chaplin and others, audiences could celebrate the ability of screen performers to preserve their humanity vis-à-vis technical equipment. Rehearsing and recalibrating human beings’ relationship with the apparatus, film facilitated a collective habituation to the modern sensory-perceptual regime. For Miriam Hansen, cinema thus assumed a key function in Benjamin’s efforts “to reimagine experience under the conditions of technically mediated culture.”[3]

Yet the concept of cinematic experience is contested among Benjamin scholars. Martin Jay argues that Hansen places undue emphasis on the emancipatory potential of film spectatorship, offering an against-the-grain reading that defies the Frankfurt School’s broader narrative of a decline of experience and the public sphere.[4] Whatever the “room-for-play” once afforded by cinema, today’s neoliberal, corporatized digital mediascape gives little credence to the critical theorist’s more stubbornly utopian ideas. Revisiting Benjamin in the present moment—when ever-greater numbers of us, like film actors, perform our labor in front of a media apparatus—one is instead drawn to the negative and even militant passages in his writing. Then as now, technological media are serving the exploitative interests of a narrow elite, and “the expropriation of […] capital is an urgent demand for the proletariat.”[5]

[1] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, in Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 115.

[2] Ibid., 108.

[3] Miriam Bratu Hansen, Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 130.

[4] Martin Jay, “The Little Shopgirls Enter the Public Sphere,” New German Critique 41, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 159–169.

[5] Benjamin, “The Work of Art,” 115.

Add new comment