Curator's Note

Caroline Martel’s The Phantom of the Operator (2004) is an archival film about women telephone operators whose voices mediated the connections between the two ends of the line before the introduction of automated switchboards. The film consists of images extracted from old corporate films that depict fictional as well as actual women operators for either training or promotional purposes. Throughout the film, these archival images are accompanied by the unseen soliloquizing voice of a fictional woman telephone operator created by Martel.

The archival excerpts from the corporate films draw attention to the ways in which the industry aimed to standardize the operators’ voices in compliance with the heteronormative ideals of femininity at the time and thus to suspend diverse vocal idiosyncrasies among them. Via the fictional operator’s voiceover soliloquy, the revenant of a singular feminine “I” haunts in the film this vocal standardization.1

Otherwise put, The Phantom lays bare the fictional residing in the official archive (the actors playing the operators in the corporate films) and supplements the official archive with the fictional to account for a feminine singularity, which is by definition foreclosed from this archive of homogenization. In doing so, the film troubles the conventional use of the term found footage as a token of the factualness of archival visuals in contradistinction to the fictitious.

However, rather than invalidating it, the film mobilizes another understanding of foundness, which, on the one hand, reveals the factuality of the found as always-already mediated through the fictionality of power dynamics, and, on the other, creates room for alternative fictional supplements that attend to the excluded from (within) the found.2

As an alternative fictional supplement to the foundness of the archival, the voiceover soliloquy welcomes in the film the other archive 3 that displaces the official archive of the telephonic standardization of femininity from within by gesturing towards singularities that are silenced by, yet hover within the operators’ uniformized voices.

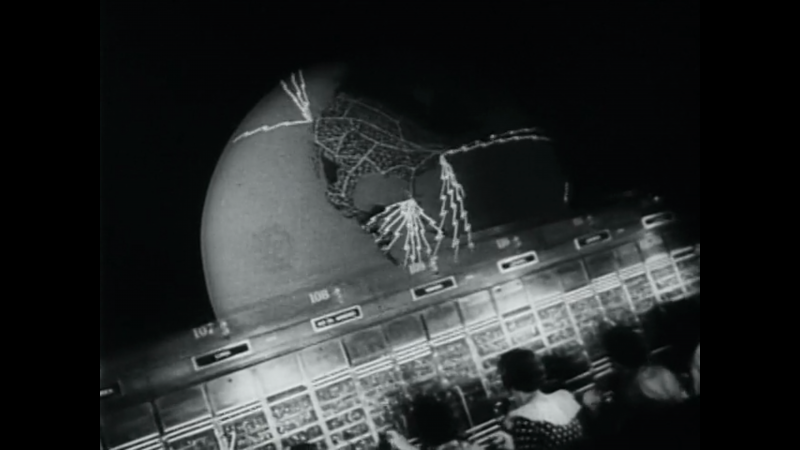

At stake here is the tension between the two manifestations of the tele-phonic as the voice traversing spatiotemporal boundaries via technological mediation (the virtual images of the globe in the film are visual counterparts of this unbounded vocality): (1) the tele-phonics imposed on the operators is meant to establish transcendentally monophonic and univocal femininity; (2) by contrast, the tele-phonics at work in the soliloquizing feminine “I” of the voiceover foregrounds its inherent insufficiency to arrive at a transcendental sameness in terms of femininity, thereby underlining the interminable polyphony and equivocality in and of the feminine.4

Fictional and tele-phonic, this “I” belongs at once to any, every, and no woman telephone operator; thus, it opens itself to the singular voice of each and every operator, while also avowing its failure to encompass singularities in the face of their incalculability. To this end, remaining acousmatic while floating over the operators’ archival images throughout, the voiceover soliloquy never coincides in the film with any operator’s body. This persistent non-coincidence suggests the following: the fictional can supplement the official archive of the telephone industry to provide a vocal opening to the myriad of singular femininities repressed by this archive; nevertheless, it cannot close off this opening by including all these singular femininities in its own feminine tele-phonics conclusively.

References

1 For the concept of the singular, see Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural, trans. Robert D. Richardson and Anne E. O’Byrne (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000).

2 For a discussion on foundness in relation to archival and experimental films, see Jaimie Baron, “Introduction: History, the Archive, and the Appropriation of the Indexical Document,” in The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (New York: Routledge, 2014), 1-15.

3 Here I am drawing on Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). See also Domietta Torlasco, The Heretical Archive: Digital Memory at the End of Film (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

4 For a philosophy of the tele-phonic, see Avital Ronell, The Telephone Book: Technology, Schizophrenia, Electric Speech (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1989).

Add new comment