Curator's Note

Red light, green light. 무궁화 꽃이 피었습니다. A globally familiar game with a universal conceit: make it to the end without being seen.

무궁화 꽃이 피었습니다. In Korean this means, “the rose of Sharon has blossomed.” An innocuous enough mistranslation, the rules of the game remain, for the most part, preserved and familiar across national boundaries. While one player chants, the others try to make it across the line the player stands on, keeping still during moments of silence. Another version of the game has the chanting player able to tag players who move during silence while the rest of the players attempt to rescue their friend from “jail”.

무궁/mugung, the hanja (Sino-root) characters for “infinity” and 화/hwa, hanja for “flower.” Literally “infinity flower.” The game and the flower alike are fables of resistance. As the flower’s history of resistance is imbued in the name, the game asks of its players to stealthily endure the constraints of the game, to endure stillness to cross the finish line. Red light, green light. It is a game that has endured time as much as it demands its players endurance.

꽃이/ggotchi is the hangeul (Korean character) for flower. Altogether 무궁화 꽃이 translates to “the rose of sharon flower” or “the hibiscus syriacus flower” in English. The flower is mentioned in the national anthem of Korea, the 애국가/ aegukga, or “The Patriotic Song.” The first known version dates back to the 1890s and was subversively sung during the Japanese Occupation of Korea. The refrain of the song is "무궁화 삼천리 화려강 산" or “three thousand ri [unit of measurement] of splendid rivers and mountains covered with mugunghwa blossoms” (“The National Anthem”).

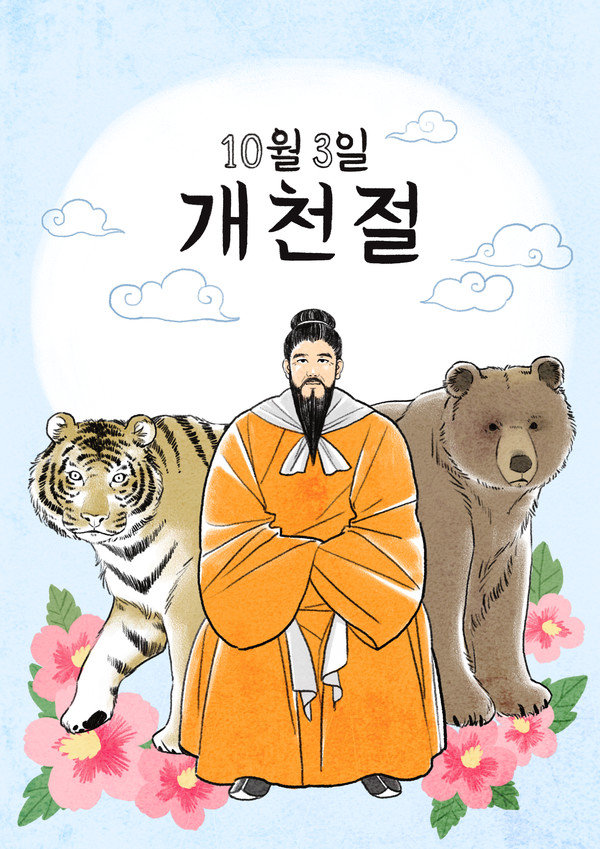

The Rose of Sharon is the national flower of Korea, it has been officially since liberation in 1945. It is a flower which commingles nationalism and historic pride–the Silla Dynasty was known as “the Country of the Mugunghwa” and mythological founder of Korea, Danggun, is often shown with the flower. The Chinese even once bestowed the charming title of “the land of gentlemen where mugunghwa blooms” when referencing Korea (Manoa).

Fig. 1. A drawing celebrating the Korean National Founders Day detailing Danggun, mythical founder of Korea, and a tiger and bear from the Korean origin myth atop a bed ofmugunghwas.

Fig. 1. A drawing celebrating the Korean National Founders Day detailing Danggun, mythical founder of Korea, and a tiger and bear from the Korean origin myth atop a bed ofmugunghwas.

피었습니다/ pi-us-eumnida, which means “has blossomed.” The mugunghwa is a robust Spring flower–it will bloom as long as through August. It’s a flower recognized for its ease in replanting and environmental endurance. Symbolically, it’s easy to understand why a newly liberated country, historically proud of and coupled with the flower, would bestow the honor of national flower onto the mugunghwa.

David Fedman, in his book Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea recenters Korean colonization through Japan’s forestry and afforestation policies. Korean trees were ritually destroyed, either from overuse during Japan’s military involvement during WWII, or as a form of environmental and social control. Japanese forestry rules and requirements were instituted in place of existing Korean codes; the Korean landscape gradually replanted with Japanese flora and fauna: the mugunghwa in exchange for the cherry blossom.

The popular children’s fiction book When My Name was Keoko, which details the social reality of Japanese colonization through the eyes of its young Korean protagonist, narrates how the family must hide their Rose of Sharon tree when the Japanese soldiers in the neighborhood begin routinely destroying them. It survives past colonization and becomes symbolic in the book (and nation) for Korean resistance, determination, and nationalism during colonization.

The little girl chants: "무궁화 꽃이 피었습니다".

The little girl is Younghee, half of the duo Chulsoo and Younghee, characters from Korean children’s textbooks. Their first appearance corresponds with the birth of Korean textbooks; 국어 1-1 or literally “Korean 1-1” was published in 1948 and corresponding iterations remained actively published and taught through the Korean War and continue to be popular characters in textbooks and memory.

Fig. 2. Younghee and Chulsoo on the cover of a 1960 국어 1-1 [Korean 1-1] textbook.

Fig. 2. Younghee and Chulsoo on the cover of a 1960 국어 1-1 [Korean 1-1] textbook. The first game in the series itself is laden with nostalgia: the giant doll is intentionally reminiscent of the children’s textbook character Younghee, a character who has endured wars and revolutions. Coupled with a nostalgic childhood game and its refrain it becomes imbued with the nostalgia of nationalism.

As the action of the scene unfolds, the nostalgic past turns into something deadly. Two players make bets over who will cross the line fastest. One takes off with reckless abandon, clearly bodily familiar with the game. The game catches him off balance. He is shot. Comfort meets confusion: a childhood game stood hand in hand with a childhood character. But the game is too literal now and takes its historical meaning too seriously. It demands the participants endure.

Most Korean schools have an outdoor playground for physical play and physical education. In Korean schools, air raid drills are conducted on the school playground, an often dirt/sand-packed field with field lines painted on. Children gather in uniform (the uniforms in Squid Game are strikingly similar to Korean gym uniforms). Games in the postcolonial Korean condition are conducted on the very grounds we prepare for a war which has not ended.

Younghee’s eyes become scopes to shoot targets. Guns appear from within the walls; attracted to movement they shoot every rogue player desperate to survive. Guns on walls. Guns on blue walls. The blue walls stretch high above the field, eventually blurring and blending with the sky in this fabricated space of play.

The schoolground is militarized in this moment of movement. Suddenly Korean preservation tactics during the colonial past (the enduring mugunghwa) become conflated with another kind of preservation tactic in the postcolonial present: border crossing. Those in the game who have gone “rogue”, who panic and refuse the rules of the game are hunted and shot systematically by guns tracking movement in walls as soldiers who defect and attempt to cross the DMZ must survive the supposedly lethal shoot to kill orders (Choe; “North Korea”). Yet those who survive the cross sometimes endure it once more when faced with the marginalized condition of seeking refuge in the hyper-competitive Korean society (Choe). A hyper-competitive society which has in-part flourished off the backbone of rigid and competitive educational standards and structures.

In this first of many games in the series we encounter a cacophony of violences: we meet a history of Japanese afforestation politics, a practice of mundane and daily violence against the Korean landscape, agricultural workers, and its peoples. This is conflated with the everyday and violent presence of partition, of a man-made wall which continues to be defined by securitization, surveillance, and policing. A wall which symbolically represents the political relationship of two nations, and the historical movements which led to them. The participants remain the downtrodden, the refugees, the migrant workers, those who collect the nation’s debt, and those who wish to escape it entirely. But they are also the everyday citizen: the children who play on the school playground, for fun or for futurity.

Let’s consider the other version of the game played in contemporary Korea. If a player accidentally moves after the speaker has stopped talking, that person must remain in their spot until another teammate rescues them. In a commingling of red light, green light and tag, the game is supposed to reinforce camaraderie.

If one takes a step back, they are surrounded with images of communal activity: a national flower which symbolizes the perseverance and resistance of Koreans during colonialism; a childhood textbook character which has been taught in Korean classrooms for decades; a game played collectively as much as individually; a school field surrounded by children’s gym uniforms.

As the series progresses, the participants become even more cutthroat and independent. They discard morals, ethics, and each other in their pursuit of egregious fortune. As players hide behind the bodies of other players they become the antipathy of the mugunghwa. Korea’s national, collective past becomes weaponized against these players in the pursuit of unfathomable capital gain. Nostalgia has become a weapon; once a rallying cry, the mugunghwa appears a threat to individuals forced (or voluntarily) playing the game. Squid Game show us that just as our childhood has turned against us, we find that we have failed our childhood long before. Perhaps we only realized it when we were willing to capitalize on our childhood, our communal histories and memories, and get slapped for one more chance at wealth.

References

Choe, Sang-Hun. “To Reach South Korea, He Risked His Life. To Leave It, He Did It Again.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Jan. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/06/world/asia/north-korea-defector-dmz.h...

Fedman, David. Seeds of Control: Japan's Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea. University of Washington Press, 2020.

Manoa, vol. 14 no. 2, 2002, p. 34-34. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/man.2003.0044)

“North Korea 'Killed and Burned South Korean Official'.” BBC News, BBC, 24 Sept. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-54275649.

Park, Linda Sue. When My Name Was Keoko. Queensland University Press, 2013.

“The National Anthem - Aegukga.” Ministry of the Interior and Safety, MOIS, https://mois.go.kr/eng/sub/a03/nationalSymbol_2/screen.do.

Images in order of appearance:

“단군왕검이 고조선을 건국한 10월3일은 개천절로 지정되어 기념하고 있다.” [October 3rd, when King Danggun founded Gojoseon, has been designated and celebrated (as a holiday).] SideView, 3 March 2020, http://www.sideview.co.kr.

오스테. Auste. “내가 가진 책 중 가장 나이든 책.” [“The Oldest Book in My Family.] Auste’s Intermediate World, 4 April 2010, http://auste.egloos.com/v/2537668.

“Red Light, Green Light.” Squid Game, created by Dong-Hyuk Hwang, season 1, episode 1, Netflix, Sept. 2021.

Add new comment