A strong sense of community within a hybrid cohort can have a huge impact on collaborative work. Yet how do we foster that connection? Within my own hybrid cohort, a certain congeniality evolved concurrent to our studies. As we made each other laugh, were we simply goofing off? Possibly. Did that playful interaction support our scholarly productivity? Certainly.

Collaborative play via humor impacts the efforts of online communities, promoting networking and encouraging communication by decreasing the fear of judgment (Griffin 88). As more institutions conduct joint work online, a rapid style of witty and self-referential exchange emerges as an important strategy for fostering creative thinking. During the invention process, seemingly benign exchanges belie a complex social task. Participants often quickly transfer ideas, filtering through the safety net of wit. Simultaneously, participants demonstrate various types of knowledge through humor. Within a chat or a shared document, students offer ideas and critique, couched in friendly banter and witticisms, demonstrating their scholarly prowess while attempting to shield possible vulnerabilities.

In such situations, participants are typically unable to hide behind anonymity. One must then consider how this alters the use of humor. In the example of an academic proposal, are there high stakes for scholars who must identify themselves? Does humor offer a safeguard for potential missteps in the performance of academic prowess? The graduate experience is an opportunity to foster professional social networks that will extend into one’s academic career. Thus, friendships, or lack thereof, may have professional consequences. The act of collaborative invention may challenge such connections as students must offer ideas that may not yet be fully formulated, or provide constructive criticism in response to others’ work. This creates the necessity for careful negotiation by each scholar, in order to perform the task while retaining his place within the community.

Several theories begin to address the multifaceted aspects of humor and identity performance. First, one may turn to the sociolinguistic theory of “face.” In “Interpersonal Politeness and Power,” Ron and Suzanne Scollon define “face” as, “The negotiated public image, mutually granted each other by participants in a communicative event” (45). However, all communication carries some risk. In “Compliments and Politeness in Peer-review Texts,” Donna Johnson acknowledges the tensions inherent to the peer-review experience, describing it as a “face threatening act” or FTA (54). Her primary interest is in the function and formulaic nature of compliments in such texts. The compliment becomes a tool that enables colleagues to critique one another’s work while maintaining a positive rapport. In order to successfully resolve the tensions of involvement and independence, humor may serve a similar function, masking critique and therefore leading to community solidarity or even group hierarchy.

The complexity of graduate interaction online is apparent in a small case study involving four graduate students, myself included. Interpersonal dynamics influences their responses, yet compliments do not dominate the interaction. Rather, the participants use humor as a means of engaging one another while attempting to avoid “face-threatening” moments.

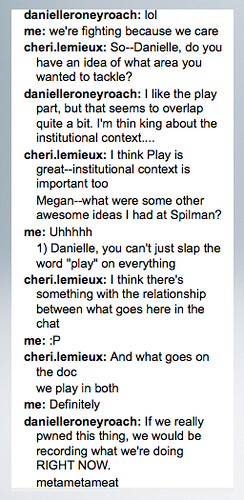

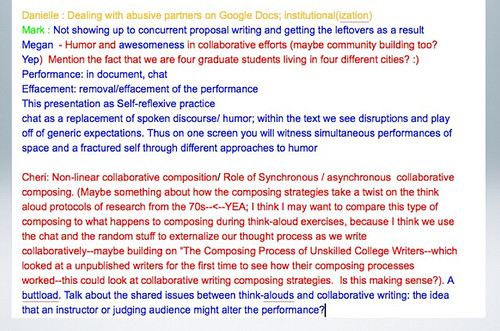

As the students work concurrently, differences emerge between the conversational tenor of the chat window versus the humor within the document. The difference implies that the students perceive these as distinct spaces on a single screen. For instance, the chat remains informal, sometimes going off topic, with the students rapidly responding. The students perform solidarity throughout the chat, with each claiming familiarity with one another. One states, “We’re fighting because we care.” Slang slips into the conversation, as another comments, “If we really pwned this thing, we would be recording what we’re doing RIGHT NOW. Metametameat” (Figure 1). The allusion to “meta” mocks an emphasis in academia for self-reflexivity. The ending typo “meat” leads to much ribbing from the other students; the self-acknowledged typo and the teasing following it are clear indicators of insider status and acceptance. Another example of a critique cased in humor appears when one student teasingly cautions another, “You can’t just slap the word ‘play’ on everything" (Figure 2).

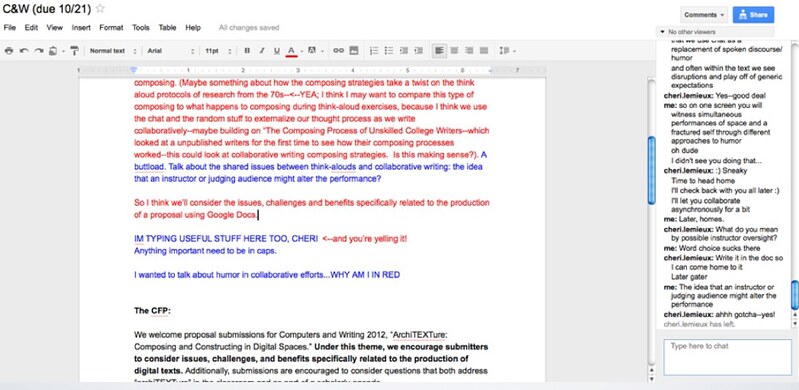

The document itself is a complex creation. In order to clearly delineate each speaker, students selected colored fonts. Then, intermingled with the serious academic discussion is a heavy amount of playful conversation, much of which either works to build interpersonal connections or to mock generic conventions. The response time may be much slower within the document, with students responding up to days later when working individually. The humor remains informal, but is more directly focused on the work at hand than the humor in the chat. For instance, when one student asks if her ideas make sense, another responds, “A buttload” (Figure 3). The playful language softens the moment of vulnerability displayed by the first student. When one student pours several ideas out rapidly, another interrupts, “IM TYPING USEFUL STUFF HERE TOO,” to which the prolific student responds, “<--and you’re yelling it!” The exchange is concluded as the first comments, “Anything important needs to be in caps” (Figure 3). Here, one may witness the students riffing on formal elements of writing and the ways that it might be violated, while overlooking the domination of one student and the possibly rude interruption of another. Notably, the proposal in question was successfully submitted and presented at Computers and Writing 2012; this very article comes from the same collaborative exercise.

There are possible pedagogical implications for such a line of inquiry. Humor can serve many functions in the composition process, including: promoting community building, encouraging the exchange of ideas, decreasing the fear of judgment, allowing the creation of multiple spaces, permitting fluid constructions of identity, and enabling creativity and productivity. Notably, in academic work, the humor is often actively erased from the final product. The intentional effacement of invention humor adds to the academic performance, yet has negative consequences for our understanding of collaborative composition.

Finally, this brief example suggests another line of questioning. As these online communities, such as hybrid cohorts, share ideas and possibly values, does humor in the online forum become a homogenizing force? As seen with the theories of face and politeness strategies, humor can be one way to navigate potential social missteps. At the same, many of the examples demonstrate trends towards enforcing communal similarity. Thus, we must be careful not to overlook humor's function as it offers both the opportunity for creativity as well as the possibility for conformity in our online interactions.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Works Cited

Griffin, Jo Ann. "Exit Laughing: Persuasive Reform Humor of Three Nineteen- Century Women." Masters Thesis. University of Louisville, 2003.

Johnson, Donna M. “Compliments and Politeness in Peer-review Texts” Applied Linguistics. University of Arizona 1992: 51-71. Print.

Scollon, Ron and Suzanne. “Interpersonal Politeness and Power.” Intercultural Communication. Malden, MA: Blackwell 2001: 43-59. Print.

Comments

Check your ego at the door por favor

I wouldn't think humor as homogenizing force since people have different types of humor. However, if we are constantly checking ourselves and worrying that the motivations behind our online commentary are understood, maybe we risk compromising humor and bombing altogether. Although struggle is great fuel for knowledge development, I sometimes worry that the preservation of ego drowns out many opportunities for recognizing meaning.

Again, humor is still a great way to check one another as well as oneself. Furthermore, it's a necessary release before jumping into the arena of Academic BS.

Humor as homogenizer

I think the idea that humor possibly directs us toward conformity is an interesting one, not only in academic communities but just in communities in general. For example, I'm a Jon Stewart fan, and so I occasionally post some of his bits on Facebook because I think his political commentary can be scathingly funny. Every once in a while, though, I have a run-in with my more conservative friends and family members because they do not think he's funny AT ALL. In fact, I've been directed to many resources, like the "Jon Stewart is Not Funny" Facebook site, to convince me that he's not only un-funny but also hypocritical and even un-American.

In this situation, then, humor homogenizes two groups at the same time: it unites those who want to be seen as supporters/members of a certain political identity/philosophy while simultaneously distancing those who don't identify with that identity into a no-less-homogenous camp of their own. Arguably, I guess, this happens with all humor, where the audience splits between those who laugh and those who don't. So then, I would think making this "work" for us in classrooms hinges both on accounting for that underbelly and then on finding ways to talk to students about the intricacies of this process without "over-explaining the joke," so to speak. I think Megan's analysis here is a great example of how to do just that, one that can serve as a model for use in classrooms at many levels.

Add new comment