Creator's Statement

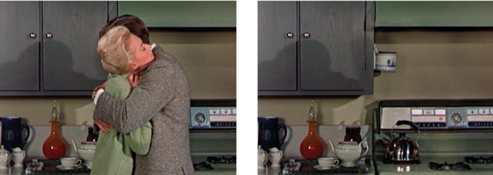

This video aims at creating an alternative experience of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), emphasizing issues of legibility, composition, and narration. I started by selecting a small set of frames of Hitchcock’s film and then I digitally manipulated the images by erasing the figures. The digital stills were recombined with fragments of the original soundtrack, creating a dissociative relation between image and sound, movement and fixity. As a result, the apparent neutrality of each frame is transformed into a distorted and uncanny vision that depicts empty sets inhabited by ghostly presences.

Through these formal solutions I tried to disrupt the diegetic principles and the dramaturgical formulas of the narrative, bringing to the fore sets of virtual and mental relations that exceed the sequence of actions in space. For Gilles Deleuze, this later aspect constitutes “the source of the very special sense of frame” in Hitchcock’s cinematography: according to Deleuze, “the frame is like the posts which hold the warp threads, whilst the action constitutes merely the mobile shuttle which passes above and below” (Deleuze 1986: 200). By creating a tension between the stilling of the moving image and the movement of the narrative associated to the soundtrack, I aimed to underline this very idea of frames acting like posts. Nonetheless, the video’s purpose is not to retell fragments of the story, but to produce a disjunctive temporality that overlaps different rhythms and durations, partially covering and partially revealing singular aspects of the narrative.

By opening the video with the Bodega Bay sequence, I also allude to Raymond Bellour’s theoretical essay System of a Fragment (on The Birds), originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma in 1969. Similarly, Bellour’s essay makes use of still frames in order to reinterpret and rediscover the film. Nonetheless, Bellour uses the stills as minimal units of signification that follow the order of the plot in a systematic fashion (Bellour 2000: 28), emerging as illustrations of a closed argument presented in written form. The cutting-up of the filmic chain into narrative units (shots and sequences), described by Bellour in terms of specific codes and textual relations, exposes the functioning of a “cinematic text” (Bellour 2000: 29), a textual system organized around demarcated structures of identification, sexual difference, and fetishist vision (Bellour 2000: 59).

It is precisely against such deterministic and univocal interpretation of classical cinema (in general) and of Hitchcock’s The Birds (in particular) that the present video is constructed. The video reacts against views that impose meaning and control upon the images through written close textual analysis. It challenges the idea that the meaning of the film exclusively depends on syntactic procedures and binary oppositions, reflected on Bellour’s fixed categories of framing (close/distant); camera movement (still/moving); and point of view (seeing/seen). In sum, this video is less interested in the study of codes in film semiotics, related to what Christian Metz termed, in Language and Cinema, as the “principle of coherence” of the filmic text (Metz 1974: 75), than in the enactment of situations of estrangement and discontinuity that explore the gaps and the intervals of the narrative.

It has to be observed, though, that at least since the mid-1970s Bellour shifted his earlier efforts to understand specific codes of classical movies to an approach that privileged the material and transdisciplinary aspects of film. In his introduction to L’Entre-Images: Photo, Cinéma, Vidéo (2002), Bellour stresses the idea that the interruption of movement enabled by video is part of the most intimate and profound experience of film. Its intensity consists in removing something from the action, from the continuity of movement, revealing a visual experience connected to the mutation of the image (Bellour 2002: 13). Already in The Unattainable Text, originally published in 1975, Bellour argued that the still is a form of quotation: despite its inability to reproduce the sense of movement, the freeze frame opens up the “textuality” of the film, a concept that Bellour loosely connects to Roland Barthes’s categories of work and text. In From Work to Text (1971), Barthes argues that unlike the work, which is a closed object, the text is opened-ended, achieving its full effect only in the act of being read and transformed through playful and innovative associations. Thus, Bellour discovers another potentiality of the still image. The still is not anymore a minimal unit of signification within a system of signs. It does not merely function as the illustration of a closed argument. On the contrary, it allows for the quotation of what is “unquotable” in the film (Bellour 2000: 20). This is what Barthes, in The Third Meaning (1970), conceived of as the potentiality of the still to grasp an “’indescribable’ meaning” that shatters the logical time and the diegetic relations structured by language and visual grammar (Barthes 1970: 68).

A singular characteristic of the proposed video is that the effect of de-composition of the narrative is entirely achieved through the processes of quotation and re-contextualization of the images and sounds that compose the original film. In this sense, the low quality of the video and the use of slightly cropped images should be understood as processual and performative elements of the videographic writing. I was not interested in producing flawless and sharpened images. On the contrary, I opted to affirm the blurry and raw materiality of those second-hand images, revealing the processes of copying and quoting as performative actions through which the images are incorporated, transcribed, transformed, and re-elaborated in an alternative composition. In this sense, video emerges as a hybrid space of representation that enables me to explore what Régis Durand termed as “subliminal images” (1995: 176), placed between movement and fixity, placed between the construction of meaning and the collapse of conventional forms of interpretation and identification.

In Hitchcock’s The Birds there is a question that remains unanswered, reflecting the existence of a non-sense that disrupts the story: why do the birds attack? As argued by Slavoj Zizek (1970), "it is not enough to say that the birds are part of the natural set up of reality. It is rather as if a foreign dimension intrudes that literally tears apart reality". Paraphrasing Zizek, the symbolic space is disturbed, and reality disintegrates, undermining the fabric of what we experience as reality. Also for Deleuze, whenever the birds attack the relationship between man and reality is radically disarranged: the whole becomes “the perception of a whole of birds, testifying to an entirely bird-centred Nature; turned against Man in infinite anticipation” (Deleuze 1986: 20).

By selecting and transforming a number of frames and by de-composing the narrative, I intended to give visibility to such distorted and unexplainable reality through purely visual and sound relations. As Deleuze puts it, the question does not any longer concern what will be the next image, but rather what is there to be seen (and heard) in the image. This is an image that, according to Deleuze, “is legible as well as visible” (Deleuze 1986: 12). Through the quotation and reconfiguration of expressive cinematographic elements that are already components of the film, the video enables the circulation between what is latent and manifest, visible and invisible, attainable and unattainable, allowing the viewer to navigate the film in an entirely new way. It is this reciprocity between different structural levels (which also include the illustrations of the present statement) that should be preserved, and not a clear opposition between the original film and the quoted film.

The video also deals with the memory of the film, since the selected images and sounds act as clues from which each spectator reconstructs her/his previous experience of the film. In this regard, it is worth to notice that the digital erasure of the figures was obtained through the superposition of several frames and camera perspectives, emphasizing the idea of a vertical structure that enables the viewers to shape and reshape their experience of Hitchcock’s The Birds. What is at stake here is, once again, the existence of a dynamic difference between what is seen and remembered, between what is erased and made visible.Thus, by combining different media and by subverting viewers’ normal expectations, the video attempts to signal the existence of another film, allowing the viewers to experience and to think its textuality in purely cinematic terms.

References

Barthes, Roland. “The Third Meaning”. In Image, Music, Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. London: Fontana Press, 1977, pp.52-68.

Barthes, Roland. “From Work to Text”. In Image, Music, Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. London: Fontana Press, 1977, pp.155-164.

Bellour, Raymond. "The Unattainable Text". In The Analysis of Film. Ed. Constance Penley. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000, pp. 21-27.

Bellour, Raymond. "System of a Fragment (on The Birds)". In The Analysis of Film. Ed. Constance Penley. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000, pp. 28-68.

Bellour, Raymond. L’Entre Images 1: Photo, Cinéma, Vidéo. Paris: La Différence, 1990.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1. The Movement-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1986.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1989.

Durand, Régis. Le Temps de L’Image. Paris: La Différence, 1995.

Metz, Christian. Language and Cinema. The Hage: Mouton & Co. N.V., 1974.

Zizek, Slavoj. The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (documentary directed by Sophie Fiennes; written by Slavoj Zizek). Vienna and London: Mischief Films/Amoeba Film, 2006.

Bio

Miguel Mesquita Duarte (PhD) is a member of the Institute of Art History, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa. His research interests include archival art, memory and history, voyeurism, counter-narrativity in documentary films, and the relationship between moving images, photography and writing. He published on Gerhard Richter’s Atlas in the RIHA Journal; the ethics of remembering and the cinema of Heddy Honigmann in Studies in Documentary Film; and archive, memory and Portuguese photography in Photographies (with Bruno Marques). He is the author of the book Imagem de Arquivo e Tempo Mnemotécnico: Para um Projecto de Arquiviologia na História da Arte / Archival Image and Mnemonic Time: For an Archiviology Project in Art History, Covilhã: LabCom.IFP Books, University of Beira Interior, 2018.

Add new comment