Creator's Statement

Note: Extending the dialogical structure of the video as well as its visual approach to attribution, Guillaume's words are presented here in italics and Chloé's in roman.

GeoMarkr is partially based on a paper I originally wrote for the September 2021 issue of the French journal Immersion about 'videogames and borders'.[1] Though my research focuses on spatial representation in computer games, it took me a long time to figure out which aspects of the question I wanted to address, and what game I wanted to write about. At the time, we were experiencing successive Covid-19 lockdowns, and I found myself playing GeoGuessr a lot with friends of mine; but because of its 'browser game' hybrid nature, and the relative poorness of its gameplay mechanics, it didn’t immediately strike me as a legitimate candidate.

It was during the writing of that Immersion paper that Guillaume introduced me to GeoGuessr. My initial experiences with the game weren't very successful, but it captured my scholarly interest. My research aims primarily at the creative study of online media practices, and I was intrigued by the simple yet efficient way in which GeoGuessr gamified the Google Street View interface.

Talking with Chloé, I later realized that it was precisely GeoGuessr’s 'borderline' experience of online navigation, and the importance it had in my spatially confined life, that made it particularly interesting. The original text was an 8-page long experimental essay, which included subjective first-person reflection mixed with bits of in-game audio recording transcripts. Considering how important the social online multiplayer dimension of the game was in my experience, I wanted to include these verbatim dialogues and use their strange indexicality (they are basically impossible to understand without any visual context) to put the reader in position similar to the player’s: you have to figure out where you are with a limited amount of clues. I also wanted to reflect on the meta-communicative aspect of these gaming dialogues: their hard-to-understand nature was meant to underline how, at the time, the mere fact of talking to each other was more important than what was being talked about.

The documentary quality of these conversation transcripts immediately made me imagine responding to Guillaume's paper with an audiovisual piece. He procured the audio files for me and I was struck by their texture: the geographical distance between the players as well as the multiple layers of technological mediation that enabled their interaction were inscribed in the very sounds of the game – the difference in quality between their voices, the clicking and keyboard sounds.

A believer in the affordances of experimental montage as a technique to produce critical insights about audiovisual objects,[2] I soon imagined bringing Guillaume's discussion of GeoGuessr in conversation with the filmography of Chris Marker. Two elements convinced me to do so: the unmistakable importance of travels in Marker's filmography,[3] and his interest for Internet environments and video games.[4] These thematic connections made me want to explore what Marker’s films could teach us about GeoGuessr - and vice versa. The video's form then developed organically as I explored visual commonalities and disparities among the material I had collected, following a process that I relate to Catherine Grant's notion of 'material thinking'.[5]

In hindsight, I would describe my method and objectives as two-fold. First, I explored the visual language of the GeoGuessr interface by applying some of its operations onto Marker's footage. This is especially visible in the five ingame sequences, for which I added to Marker images the typical jump-forward-and-freeze movement of Google Street View. The goal wasn’t to produce a perfect replica of the GeoGessr aesthetics, but to extract just a few components of its visual language – of which I became more aware through discovering which editing tools were necessary for their recreation. I wanted to present these visual operations with just enough of an estrangement effect,[6] so that viewers could notice them, and observe how much of an impact they have on the relationships we establish with the very real spaces to which platforms such as GeoGuessr and Google Street View give us a digital access.

Conversely I also tried to apply what one could call 'Markerian operations' to GeoGuessr footage. This is most obvious in the sequence in which an animated car – or spaceship – is superimposed on a screen recording from Google Street View. But many other features of our video were also borrowed from Marker: a certain approach to essayistic writing, mixing casually delivered anecdotes with analytical insights; what André Bazin called 'horizontal montage' – an editing technique which gives prevalence to words over images;[7] the distortion of the piano recording was itself inspired by Marker's experiments with electronic deformative tools. These borrowings weren't performed so as to produce a tribute to Marker's style, but as 'variations' on his filmmaking techniques – a term of musical origin that I have suggested elsewhere can be used to denote critical and creative re-interpretations of existing audiovisual forms.[8] The notion of 'variation' also informed the choice of the soundtrack, a piece by Erik Satie called Vexations composed of a short melodic theme and two variations. The piece was originally meant to be played as a loop no less than 840 times, which has historically required musicians who have interpreted the piece to play between 14 and 35 consecutive hours. The loop is only heard a few times in our video, but I was interested that its insistent reiteration would echo the repetitive play mechanics of GeoGuessr (and my repeated viewings of Chris Marker's films).

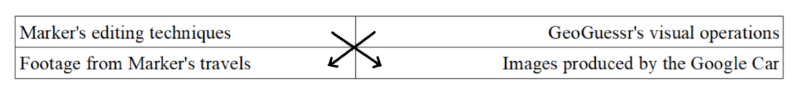

Overall one could map the videographic operations performed in this video as follows:

Methodologically, this can be compared to Ariel Avissar's experimentations in his What is Neo-Synderism?, for which he extracted the editing protocol from an existing video (kogonada's What is Neorealism?) and applied it to new footage (the two versions of Justice League by Zack Snyder), so as to perform a critical analysis of both Snyder's films and kogonada's videographic method.[9] GeoMarkr redoubles this approach by offering a cross-analysis of the visual operations of the GeoGuessr interface and the filmmaking methods of Chris Marker, investing simultaneously the two corpuses as both images and visual protocols to be analyzed.

What I find very compelling about Chloé's work in this video is that it amplifies in a personal way the communication aspect that was central to the original text, adding their own voice, as well as Marker's, to the original dialogue between M. and me. It is a point long made in game studies that games have a 'social function' and participate in a form of communal dialogue.[10] The video also embraces the playful nature of its subject: like GeoGuessr players, viewers are invited to locate themselves in the polyphony of voices that are heard and read (each speaker identified with a different font color), as well as in Marker's filmography and are rewarded – in a very welcoming way – with the solution to the puzzle in the end credits.

I thought long about the decision not to indicate the titles of Marker's films as they appear on screen. It was important to me that our essay would be accessible to viewers who aren't so familiar with his filmography that they would be able to recognize all (or any) of the original sources. But I finally decided that the above-described estrangement effect would be more powerful if it emerged from a sense of relative confusion as to the origins of the footage. I opted for not using watermarks during the film, but I indicate all the sources in the end credits. This decision was also informed by Marker's own approach to found footage filmmaking and credit attribution. As early as 1949, he declared that it is 'much easier to express oneself through other people’s texts as with one’s own';[11] fifty years later, his multimedia project Immemory invited viewers to create their own path through his audiovisual archives, made of images he had filmed as much as images he had seen.[12] Producing confusion as to where things came from was one of his signature gestures: Sans Soleil, to name only one example, features footage from several filmmakers who remain unidentified until the end credits, in which he also uses several aliases for himself. I like to think that GeoMarkr contributes to fulfilling his wish to see his practice and his labyrinthine work remembered [13] – not so much as an authoritative heritage to be revered, but as a living archive to be traveled through, reactivated and indeed played with, available to all among us who have learnt from his passion for 'bricolage'.[14]

Endnotes

[1] The presentation of the journal issue is available here: https://immersion-revue.fr/numeros/immersion-6-frontieres/.

[2] This theoretical and practical belief, shared today by many videographic researchers, can be said to find roots in Chris Marker's own practice of montage, described by Nora Alter as 'seek[ing] commonalities through unusual and unpredictable […] juxtapositions'. Nora Alter, Chris Marker, Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2006, p. 6.

[3] This can be observed not only in Marker's most famous works – Timothy Corrigan noted that 'Marker’s Letter from Siberia [1957] can be considered one of the first cinematic travel essays and his Sunless [1983] one of the most ambitious and complex journeys around the world' – but in the entirety of his filmography: If I Had Four Camels [1966] alone is said to contain images from twenty-six different countries. Timothy Corrigan, The Essay film: From Montaigne, After Marker, New York, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 105.

[4] This interest was particularly illustrated in Level Five (1997), and later in Marker’s experimentations with the online game Second Life (Linden Lab, 2003).

[5] Catherine Grant adapted the expression from Barbara Bolt to a videographic context; see Catherine Grant, 'The shudder of a cinephiliac idea? Videographic film studies practice as material thinking', ANIKI: Portuguese Journal of the Moving Image, 1 (1), 2014, p. 49-62.

[6] This also motivated my decision to respect the heterogeneous formats of Marker’s images (which span over several decades of image making technologies) instead of reframing them so as to fill a 16:9 screen. I wanted the superposition of Marker’s footage and GeoGuessr interface to be odd rather than seamless, so that viewers would become aware of the images and the visual operations to which they were subjected as two distinct entities.

[7] In horizontal montage, 'the image does not refer back to that which precedes it or to the one that follows, but laterally, to what is said about it […]. Montage is made from the ear to the eye'. The review by André Bazin of 'Lettre de Sibérie', first published in France Observateur in 1958, is presented here in the translation into English by Chris Drake, 'Chris Marker: Eyesight', Film Comment, 2003. https://www.filmcomment.com/article/chris-marker-eyesight.

[8] Chloé Galibert-Laîné, “Documenter Internet. Essais sur le réemploi d'internet dans le cinéma de non-fiction contemporain”, PhD dissertation prepared under the supervision of Antoine de Baecque and Dork Zabunyan, defended at the ENS de Paris on October 29, 2021, p. 588 et seq.

[9] Ariel Avissar, 'What is Neo-Snyderism?', [In]Transition. Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies, 9.1, 2022. http://mediacommons.org/intransition/what-neo-snyderism.

[10] See Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens. Essai sur la fonction sociale du jeu, Paris, Gallimard, 1951 [or. 1938].

[11] Full quote: 'On s’exprime beaucoup mieux par les textes des autres, vis-à-vis de qui l’on a toute liberté de choix, que par les siens propres'. Chris Marker, L’homme et sa liberté. Jeu dramatique pour la veillée, Paris, Seuil, 1949, p. 7, quoted in Maroussia Vossen, Chris Marker (le livre impossible), Paris, Le Tripode, 2016.

[12] Immemory contains, among many other sources, images from Wings (William A. Wellman, 1927), Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), Aelita (Yakov Protazanov, 1924), Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1926).

[13] The same can be said about all video essays engaging with Marker's work. In that spirit I recommend watching Luis Azevedo's Letter from Marker alongside GeoMarkr: enough images are identical in the two videos, though contextualized differently, that it produces a similar effect to the legendary sequence from Letter from Siberia, where the same sequence of images is subjected to radically different narrations. Azevedo's video is available here: https://vimeo.com/226202981.

[14] For Marker's comments about his passion for 'bricolage', see Julien Gester, “La seconde vie de Chris Marker”, Les Inrockuptibles, 2008. https://www.lesinrocks.com/cinema/la-seconde-vie-de-chris-marker-13720-29-04-2008.

Biographies

Chloé Galibert-Laîné is a French researcher and filmmaker, currently working as a Senior Researcher at the Hochschule Luzern in Switzerland. They hold a practice-based PhD from the Ecole normale supérieure de Paris (SACRe) and have taught at institutions that include the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, the Ecole des Beaux-arts in Marseille and the California Institute of the Arts. Their work explores the intersections between cinema and online media, with a particular interest for questions related to modes of spectatorship, gestures of appropriation and mediated memory. Their video essays and desktop films have shown at festivals such as IFFRotterdam, FIDMarseille, True/False Festival, transmediale, and the Ars Electronica Festival.

Guillaume Grandjean is a French video game scholar and critic. His research explores the construction and representation of space in video games, with a special interest for the evolution of level design and spatial structures in the history of the medium. Grandjean holds a PhD in Communication and Information Sciences and has taught in Literature and Communication departments at Université de Lorraine, Université Polytechnique des Hauts-de-France and Université Paris 3. He founded and led for several years InGame, the first-ever periodical research seminar dedicated to games studies in France, which brought in conversation game scholars and designers. His critical essays have been published in magazines such as Débordements, Critikat and Immersion.

Add new comment