Curator's Note

Imagine an ocean full of shrimp spies and fish police. While the notion may seem like a child’s fantasy, militaries around the world today are hoping to make this a reality. DARPA’s Persistent Aquatic Living Sensors program (PALS) is intended to “leverage or develop organisms as sensor transducers,” incorporating marine organisms into an underwater surveillance network that attempts to technologize nature for national security. Currently, funded proposals include studies of snapping shrimp, bioluminescent plankton, goliath groupers, and black sea bass.

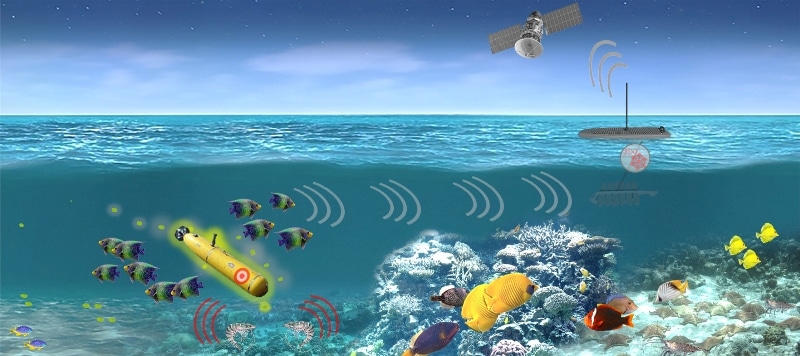

I came across PALS while researching techniques in marine biotelemetry. Indeed, larger marine mammals have already been used as sensor platforms through tagging, or the fitting of wild animals with transmitting devices through glues, clamps, darts, and other methods. Fish and plankton add a new dimension to this network—one that DARPA believes will be capable of reacting quickly to the presence of enemy submarines or criminal activity. However, while biotelemetry started with military technology that was translated into civilian scientific and conservationist efforts, in PALS, that relationship is flipped.

DARPA’s proposal of an icthyoveillance system is only one of many problematic exchanges between cultures of militarism and environmentalism in the history of oceanography. During the Cold War, the Navy engaged in military cetology programs, training and studying dolphins and whales. As John Shiga and Max Ritts explain, this introduced the language of “targets,” “budgets,” and “optimization” to describe animal communication and behavior.

Similarly, PALS selects specimens whose unique perceptual and communication techniques can be refigured in anthropocentric, utilitarian terms. Popping shrimp sounds become warning systems. Fish flight responses become detection mechanisms. The death of marine life is remediated as the death of signal. And fish become little more than drones. Indeed, Dr. Lori Adornato, PALS’s program manager justifies this work by fixating on the potential ubiquity, self-sustaining nature, and discreetness of using plankton and fish, stripping away biology and animal subjectivity in the process. Ultimately, these cross-pollinations between conservation science and security feed into the making of a carceral sea—a trend that might include the funneling of scientific sensor data into military databases, or the militarization of oceanic borders.

Add new comment