Creator's Statement

Research aims

The treatment of temporality in The Battle of Algiers is a controversial aspect of the film. Critics have noted the film’s complex sjuzhet but have argued that the film offers ‘an episodic view of history quite alien to the possibility of understanding [history] as an open horizon of possibilities and alternative realities’ (Sainsbury 1971: 7); the film is said to be guilty of an ‘excess of historical teleology’ (Khanna 2006). My own study of The Battle of Algiers, which I have taught for many years and have recently been writing about in a short book (O'Leary 2019), has convinced me that the orders of time that fashion the film are not reducible to the teleological (though that dimension is certainly there, and it is registered, wryly I hope, in the video essay). And so, work on this video essay was intended to capture something of the complexity of the film’s temporalities and to encapsulate something of the viewer’s experience of these.

Process

The essay was begun at the 2018 edition of the Scholarship in Sound and Image workshop on videographic criticism at Middlebury College, led by Christian Keathley and Jason Mittell. My working approach grew directly from the parametric exercises that were set in the first week of the workshop. These exercises (developed from those described in Keathley and Mittell 2019) imposed strict formal constraints on the choice and treatment of material to be used from the workshop participant’s chosen text. This process appealed to me for several reasons. Firstly, parametric approaches—those that deploy methods variously described in terms of ‘obstructions’, ‘oblique strategies’, ‘constraint satisfaction’ etc.—are an attested stimulus to creativity, because they are designed to bypass the preconceptions of the creator and they lend themselves to material thinking, of which videographic criticism is an excellent example.[1] Secondly, the parametric approach bracketed the idea of theme: in that first week at Middlebury, it didn’t matter what your videoessay was about, just that it was developed in a given way. This meant that you didn’t have to begin with some prior argument that you then hoped to illustrate. The formal constraints made for a genuine investigation, in other words, one that could lead to unexpected outcomes or discoveries. As Keathley and Mittell put it, ‘formal parameters lead to content discoveries’. [2] Thirdly, parametric approaches can be seen to be in opposition to the Romantic idea of the artist who expresses their essential self, or to the idea of the intellectual who authoritatively pronounces on a particular theme. Using a parametric approach, the video essayist intervenes in a system while recognising themselves to be part of that system rather than a Godlike figure beyond and independent of it.

The ‘parametric’ exercises at Middlebury involved making a ‘pechakucha’ style video on the first day, and dealt with voiceover, onscreen text, and multiscreen on the subsequent days of the first week. All these exercises informed my essay as it evolved (even if it doesn’t use authorial voiceover), but the essay’s final form was suggested by the exercise set over the weekend at the end of the first week. We were each asked to make a ‘trailer’ for our planned essays, and the final piece published here, a kind of conceptual supercut of the film’s temporalities, is an expansion of the ‘trailer’ I made. As such, it can be described in terms of advertising (the trailer) and fandom (the supercut). These are modes apparently remote from the scholarly investigation,[3] so it can justly be asked what’s academic about all this. For me, the scholarly dimension inheres in the critical impulse: as a trailer, it is a celebratory piece, but it is a critical and analytical trailer. The critical-analytical aspect is meant to emerge, not in explicit argument (via voiceover, for example), but in terms of organisation and juxtaposition; and instead of the approach that makes of the reader/viewer the passive observer of the report and illustration of an argument, I adopted one that elicits the engagement of the viewer in determining the diverse tones of the ‘discussion’.

Combination, subtraction, sequence

One of the guest mentors at the Middlebury workshop was the media theorist and practitioner Allison De Fren, who has made powerful and influential videoessays on the female body and technology in cinema.[4] Allison’s videographic approach is closer to the standard academic prose essay in which the author’s conclusions are known to herself in advance and the evidence set out in order to guide and persuade the reader. At the workshop, she was critical of the parametric approach and of the ‘poetic’ pole of videographic criticism. Thinking about and rejecting Allison’s scepticism for my own purposes, I realized I liked iterative and permutational form—the theme plus variations approach—which I think of as a formal and historical alternative in the essay tradition to the conventional argumentative form. In my essay, I allowed an accumulation of examples to replace this conventional argumentative form, and I hope my critical position and my ambivalence emerges, rather than being stated, in terms of unresolved or dialectical juxtaposition, where the relation of discrete audio, visual and textual elements must be interpreted by the viewer in the light of their knowledge of and familiarity with the film.

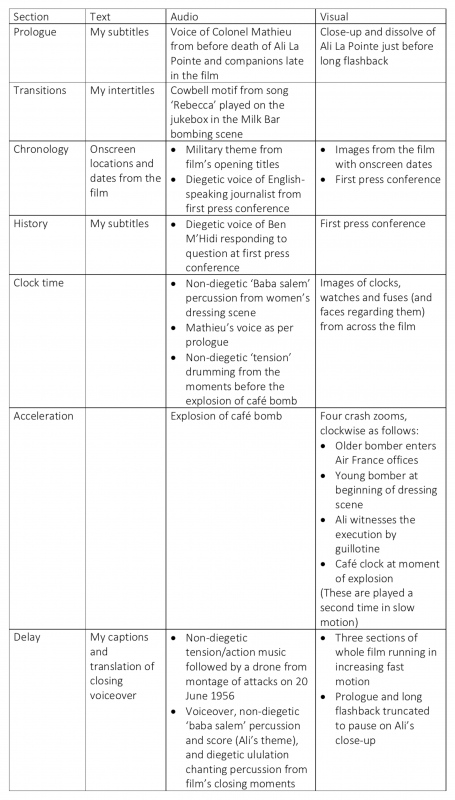

The viewer’s work of interpretation is also meant to occur ‘affectively’, or at least as reflection upon the experience of the essay rather than just upon the content (as in standard academic prose where the form is intended to be transparent if not invisible). In any case, I think of this approach as a form of immanent criticism, where the material of the film itself is remixed to reveal its structures, rhetoric, and contradictions. Thus, all audio and visual material used in the essay, apart from credits and intertitles, comes from The Battle of Algiers itself (I consider the explanatory phrases in square brackets a compromise in this respect), as set out in the table below.

One temporality not named in the essay, but which I hope to be evinced there, is ‘pace’.[5] I insisted to myself that the essay be brief yet busy in order to communicate a sense of speed. Many viewers of The Battle of Algiers describe their sense of the breathless pace of the film, of the impression of events happening in bewildering succession or juxtaposition. The viewer of this video essay, too, might experience a too-fast succession of sounds and images and of moments (or section changes) that happen ‘too soon’. Critical reflection I meant to frustrate—at least until a repeat viewing!

The brevity and speed of the piece had a consequence, however, which was that I had to avoid obtrusive vocabulary in the intertitles, except for deliberate (special) effect. The degree to which the relation of intertitle to section content was manifest or cryptic had to be calibrated to the pace of the viewing experience. Thus, ‘delay’ instead of ‘suspense’; ‘playtime’ for ‘reenactment’ or ‘carnivalesque’; and ‘mundane’ for what I might have dubbed a ‘denial of coevalness’.[6] The one title designed to arrest the viewer was ‘longue durée’: French, of course, and rare in ordinary English, though a jargon term in historiography, referring to the very long term—the history of climate, for instance. I used it here to label slow-motion images from the montage in The Battle of Algiers that shows the types of torture practiced by the French: firstly, to connote the experience of pain, which seems to dilate time when you are suffering it; secondly, to allude to the long-term experience of colonization, of which torture is the intrinsic expression. As Frantz Fanon (1969: 66) put it: ‘Torture in Algeria is not an accident, or an error, or a fault. Colonialism cannot be understood without the possibility of torturing, or violating, or of massacring. Torture is an expression and a means of the occupant-occupied relationship.’ The achronic exemplarity of the scenes in Battle’s torture montage is revealed in the light of Fanon’s remarks to refer not only to practice of torture by the French army in Algiers as part of its effort to put down insurrection in the city, but also to the long-term actuality of torture, violation and massacre that was the Algerian experience of colonization.[7] I did consider finishing this section of the video essay with the quote from Fanon (I had quotes in mind for other sections too) but in conversation with my workshop mentor, Catherine Grant, decided to stick to my rule that all material should come from the film itself. The combination of title, ‘longue durée’, with the torture images was intended, then, to evoke a long-term experience of pain and humiliation, and so to signal, in associative rather than indicative fashion, another temporality accessed by the film.

I hope not to seem to instruct in the interpretation of the video essay; I give the reasons behind the choice of one section title in order to describe my method, which was one of combination and subtraction of elements. The sequencing then became a matter of thematic, visual, or sonic continuity and contrast between individual sections. I will finish with one example of this sequencing. Each new section is signalled with a cowbell motif taken from the Spanish-language song, ‘(Hasta Mañana) Rebecca’ by the Belgian group The Chakachas, playing on the jukebox in the Milk Bar sequence when the bomb is planted in Battle, and which I use over the final section of the essay.[8] The use of a pop song in ‘Revolution’ mirrors the use in the preceding ‘longue durée’ section of a Piaf-style chanson (I haven’t been able to identify this chanson but in Battle it is part of the critique of hypocritical European leisure). In the essay, the ‘mañana’ suddenly arrives, truncating the long but not eternal durée of occupation. Tomorrow is consummated. The ‘future’ anticipated all the way through via the cowbell motif is abruptly achieved (sonically satisfied) with the end, when the song continues to play…

A final note to mention that the title of the essay, ‘Occupying Time’, was suggested by Catherine Grant. Thanks again to her for coining a title that suggests at once the colonial context, the activity undertaken by the film, and the object of the videoessay itself.

Bibliography

Fabian, Johannes (2014). Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object (New York: Columbia)

Fanon, Frantz (1969). Toward the African Revolution, trans. Haakon Chevalier (New York: Grove Press)

Grant, Catherine (2019). ‘Dissolves of Passion: Materially Thinking through Editing in Videographic Criticism’, in Christian Keathley, Jason Mittell, and Catherine Grant, The Videographic Essay: Criticism in Sound and Image (Montreal: Caboose). 65-84.

Keathley, Christian and Jason Mittell (2019). ‘Criticism in Sound and Image’, in Christian Keathley, Jason Mittell, and Catherine Grant, The Videographic Essay: Criticism in Sound and Image (Montreal: Caboose). 11-30.

Khanna, Ranjana (2006). ‘Post-Palliative: Coloniality’s Affective Dissonance’, Postcolonial Text 2:1. Available at <http://www.postcolonial.org/index.php/pct/article/viewArticle/385/815> [accessed 12 September 2017]

O'Leary, Alan (2019). The Battle of Algiers (Milian: Mimesis International).

Sainsbury, Peter (1971). ‘The Battle of Algiers’, Afterimage 3, 5-7

Tomlinson, Emily (2004). ‘“Rebirth in Sorrow”: La bataille d’Alger’, French Studies 58: 3, 357–370

van den Berg, Thomas and Miklós Kiss (2016). Film Studies in Motion: From Audiovisual Essay to Academic Research Video (Scalar/University of Groningen). Open access book available at <http://scalar.usc.edu/works/film-studies-in-motion/index>

[1] For Catherine Grant (2019: 65), videographic criticism is practice-led research that ‘knows not what it thinks before it begins; it is a coming to knowledge that is “not the awareness of a mind that holds itself aloof from the messy, hands-on business of work”, as Tim Ingold writes (following Heidegger), but, rather, “immanent in practical, perceptual activity”.

[2] Keathley and Mittell (2019: 11).

[3] I am thinking of the critique of current video essay practice in van den Berg and Kiss 2016.

[4] See ‘Ex Machina: Questioning the Human Machine’ (2017) at <https://vimeo.com/203960047> and ‘Fembot in a Red Dress’, published here on [in]Transition at <http://mediacommons.org/intransition/fembot-red-dress>.

[5] I set out my analysis of temporalities in The Battle of Algiers in standard academic terms in the chapter ’Time and Again' from my book on the film (O’Leary 2019: 83-110), and I see this video essay as a companion and complement to that chapter."

[6] ‘Denial of coevalness’ is the phrase used by Johannes Fabian (2014) to characterize how the study of another culture tends to imply that the studied culture exists in another time as well as another space, as ‘primitive’, unchanging and culturally static.

[7] Tomlinson (2004: 368) points out that the montage of scenes illustrating the different techniques of torture exists beyond the present tense of the unfolding diegesis, so that they are to be read as ‘typical’ rather than as specific instances.

[8] Interestingly, the song is an anachronism in Battle (it was actually released in 1959, whereas the bomb is planted in '56).

Comments

A Note of Clarification

Congratulations on a wonderful video essay!

I am grateful for the links to my work and happy to serve as a spur—whether positive or negative—for any discourse around videographic work. I did, however, want to clarify and nuance my position toward and approach to "videographic criticism" since what is stated above is not quite accurate.

First, I never begin working on an audiovisual essay with a pre-digested argument in mind. I was a media practitioner before becoming a scholar, and making/doing is and has always been integral to my own thinking process. While I do often formulate beforehand a motivating question or questions, I invariably begin with a material exploration of the footage I am considering, since I find that it is here where key insights are gleaned, as well as opportunities for showing rather than telling. At the Middlebury workshop, I shared my work flow in detail not only to provide one possible approach to conducting a material investigation in tandem with the creation of a script, but also to convey how interdependent the two processes are.

Second, I take no issue with either parametric exercises—which I assign regularly in my classes—or the poetic mode, which I see as forming an expressive continuum with the explanatory mode and one of the many compelling registers through which video essays produce meaning. I did, however, attempt to make a distinction between audiovisual work that is exploratory, experimental, and obversational—whose deconstructions or deformations are offered as an end in themselves—and work that charts—both through creative exploration and exposition—a distinct point of view, reading, or argument. While I see both as meaningful forms of knowledge production, the latter, for me, more readily stands on its own as academic “scholarship,” a position that is, perhaps, not unlike the sentiment that while a scholarly essay might be poetic, and a poem might be levelling criticism, a poem is generally not scholarship. Moreover, to suggest that a poem is not scholarship does not indicate criticism of either poetry or the poetic mode.

My own views and approach continue to evolve, and I appreciate the opportunity (afforded by the open-forum nature of this journal) for having these discussions.

On a related note, the Spring 2020 issue of The Cine-Files, co-edited by me and Tracy Cox-Stanton, focuses specifically on the question of what consitutes scholarship in the audiovisual essay. We hope to have a far-ranging dialogue in which multiple points of view are shared. I'll return with the link when it is published.

Workshop of Potential Scholarship

After I posted the comment above, Allison de Fren invited me to contribute to the issue of The Cine-Files on scholarship in videographic criticism that she mentions. My contribution took the form of a 500-word manifesto, along with a preface written at Allison and her co-editor's behest. In the event, the editors felt the piece didn't fit the issue and I hope it's appropriate to post it here instead, because it grows from my videoessay and creator statement and from my response to Allison's comment above.

Preface

To the extent that the question ‘What constitutes videographic scholarship?’ expresses a normative intention, I would want indefinitely to postpone an answer. If my own preference in videographic scholarship is for experimental work, I follow Paul Feyerabend in the belief that scientific and scholarly progress occurs when ‘anything goes’. And so, while my own first response to the question of what constitutes videographic scholarship was intended to be programmatic, it was not intended to be prescriptive. The editors have generously allowed me to append that first response below despite misgivings about its cryptic and gestural character: it takes the form of a playful and parametric manifesto, the context for which I try to clarify here.

I have alluded just now to a classic of Science Studies, Feyerabend’s Against Method, because Science Studies has much to teach us about how to conceive of knowledge and of scholarship—i.e., the means of accessing (note I do not say ‘producing’) and sharing knowledge. One key lesson from Science Studies in the last few decades has been to begin from what practitioners (be they scientists or videographic critics) actually do rather than from any ideal conception of what they ought to be doing (Hacking; Latour and Woolgar). For me, ‘starting from what practitioners actually do’ meant identifying, and generalising from, the scholarly poetics of videoessays I especially admire (I mention three in the manifesto). It also meant acknowledging the implications of the technology we use in our videographic practice. One can think of editing apps in terms of their affordances—what they allow—but also in terms of their agency—what they want to create. I would argue that we don’t use tech, we collaborate with non-human actors, and my own preference for a parametric approach is intended to signal the de-centred place of the human scholar (no longer the authority, but a colleague or co-actant) in this knowledge ecosystem.

This is to situate the non-linear editing platform in posthuman territory; as such, co-creating with/in it implies a performative rather than a representational conception of videographic scholarship. In other words, videographic criticism ‘produces’ phenomena rather than reports pre-existing facts (this is Karen Barad 101). I put that word ‘produces’ in quotes because my manifesto is informed by Rebecca Herzig’s critique of how the idea of production is fetishized in posthuman theory and in Science Studies, and my deployment of Bataille’s notions of waste, expenditure and potlatch follows hers. This is why I conceive of videographic scholarship as something like a phatic or trivial practice.

Wait—trivial? Yes indeed! The term ‘trivial’ comes from the word for the meeting of three roads: the location where gossip is exchanged, encounters happen (Oedipus kills his father where three roads meet), and where settlements tend to arise. The trivial is foundational, in other words, as long as a ‘foundation’ can be imagined as an evolving set of dynamic relations. The kind of videographic scholarship I envisage in the programmatic text that follows is concerned with—it analyses by entangling itself with—the mobile texture of this Heraclitean foundation.

Workshop of Potential Scholarship (10x50)

1.

My title alludes to OuLiPo, short for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), founded to explore constraint-based approaches to writing. OuLiPo proposed the acronym Ou-X-Po to envisage possible fields (designated by ‘x’) that might themselves adopt parametric procedures. I have in mind a videographic OuScholPo.

2.

A director of the NEH notoriously dismissed the contemporary humanities as ‘opaque, trivial and irrelevant’: for a workshop of potential scholarship this would be no insult. OuScholPo names a creative erotics of videographic practice, a scholarship that is playful and wilfully banal, experimental and performative but non-productive, even wasteful.

3.

An erotics, unlike a hermeneutics, implies a sensuous engagement with the phenomena studied, a practice Catherine Grant teaches us to recognise as material thinking. It has to do not with representing but with intervening. A scholarly poetics of making: of remix, mash-up and manipulation; not primarily interpretation or explanation.

4.

Sensuous engagement also with the tools of study, where subjectivity and agency is distributed along the editing platform and algorithmic action of generative constraints. ‘Formal parameters lead to content discoveries,’ write Keathley and Mittell, but more essential to parametric scholarship is the dissolution of the authority of the scholar-human.

5.

Bordwell said of parametric style that its themes are banal. Likewise, any insights achieved by parametric scholarship are candidly trivial, at least if stated as propositional knowledge. OuScholPo offers an experience, an immersion, sometimes an alienation: it dwells in texture and world-building and is uninterested in generalisable ‘take aways’.

6.

‘World-building’ also in the sense that a videographic erotics fashions its source (films, television, videogames etc.) in the act of scholarly intervention. OuScholPo doesn’t deal in ‘data’—facts or information treated as given; it creates (with) ‘capta’—phenomena captured by material thinking. It enacts (not extracts) the phenomena analysed.

7.

The scholarly poetics of OuScholPo are performative. This is the only sense in which it produces knowledge. The knowledge fashioned through a videographic erotics is procedural and creative rather than propositional: it suggests not ‘Given this, what do we now know?’, but ‘Having made this, what can we do next?’.

8.

OuScholPo protests the indenture of the Humanities to the idol of utility. Understand it not as knowledge production but potlatch, a practice in which precious resources are expended for pleasure or to challenge another (another human-scholar-algorithm) to outdo the act of waste in a further expenditure of creativity.

9.

Three examples to show what I mean: ‘Dissolves of Passion’ (Grant), ‘Object Oriented Breaking Bad’ (Mittell), ‘Who Ever Heard…?’ (Payne). These works share a parametric approach to form and to the selection of elements. Each performs rather than reports analysis: acts of immanent criticism that are immersive rather than explanatory.

10.

Imagine a gerundive scholarship—a ‘knowing-doing’—that goes beyond knowing-how to knowing-with. Or perhaps an unknowing: a scholarship that makes non-sense of things. OuScholPo is absurdist in method and (typically) outcome because it expresses a distributed subjectivity. It opens prospects inaccessible to the merely human scholar.

References

Numbers in square brackets refer to the ten numbered passages above. Unnumbered texts concern the preface.

Add new comment