Curator's Note

The premise of this brief intervention is quite ordinary: we live amidst screens; indeed, we might have become screens ourselves—watching, listening to, trading with, addressing, dating, consuming other screens. We experience screen anxiety, screen withdrawal, screen craving, screen exhilaration. Much of what we do on screen is labor—screen labor—in ways that could not be fully anticipated by the transactions of twentieth-century mass culture. Screen labor is often underpaid or, simply, unpaid—free.[1] The difference between working for a paycheck and working for free is inerasable and yet, in the social factory, these two kinds of work operate together.

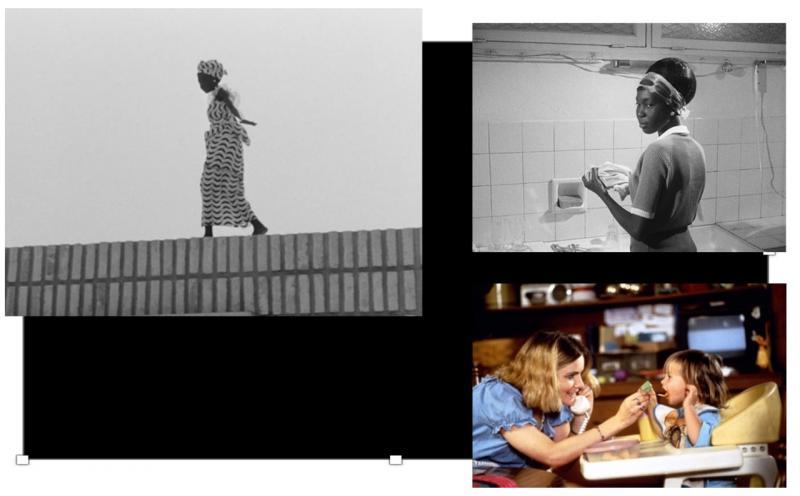

In Leben – BRD (How to Live in the FRG), ordinary people train to play themselves, they rehearse for life, on site and in person. Here they are in a childbirth class. In Zero for Conduct (Zéro de conduite), conatus is a feather.

This ubiquitous screen labor is but a form of editing—sorting, cutting, combining, reviewing, superimposing materials of all sorts. Materials are never raw and the hours we spend reworking them are seldom clocked in. This is no longer the editing of the industrial worker: “In the age of reproduction, Vertov’s famous man with the movie camera has been replaced by a woman at an editing table, baby on her lap, a twenty-four-hour shift ahead of her.”[2] The link between editing and domestic labor is neither random nor occasional. Women have always been men’s favorite editors—invisible, supplemental, multitasking ahead of the times. The film industry owns them plenty and so does the economy of so-called immaterial labor.

Screen left, in Dakar, Diouana is running barefoot atop the French wartime memorial; the man sitting down below commands her to descend. Screen right, the images are incommensurable.

Let me be clear: editing has always existed outside editing rooms and movie theatres. Eisenstein found montage at work in the Athenian acropolis and Benjamin in the cities and factories of modernity. Yet, today, editing-perception-labor have become one. Montage is more than a figure of speech: on and across digital platforms, we have all become film editors.

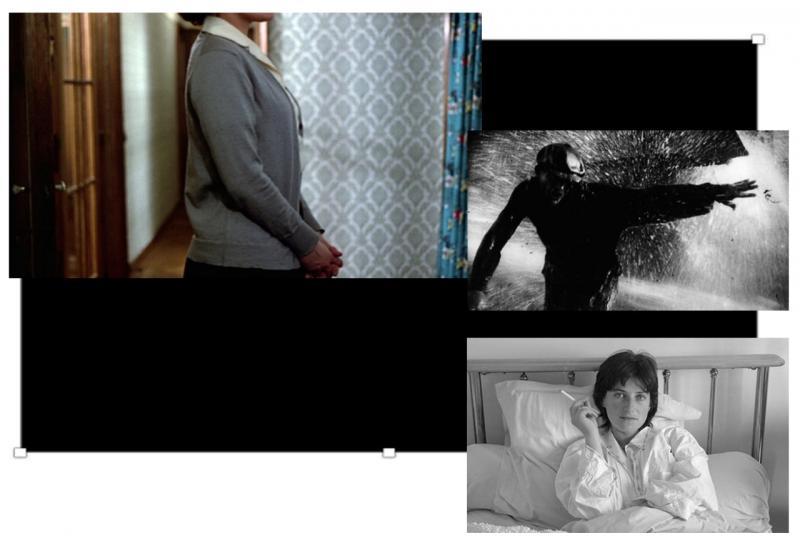

Breathing stillness: “I put the camera down, found the frame, and when I felt the shot was finished, stopped it.”[3] Montage too is a matter of breath.

How do we resist, refuse, redefine this incessant kind of labor? How do we go on strike? The situation is tricky. Screen editing has become naturalized—invisible in plain sight. Its networks are essential to the global production of needs, goods, data, peoples, desires. Walkouts and sabotage, together with the pathos of Eisenstein’s Strike, can only offer partial guidance; the interlock of production and command is always contextual and so is the strike.[4] What can we learn from cinema itself, which after all has invented itself by inventing montage?

Call for an Editing Strike is an intermedia project that begins by looking at the history of cinema and the history of feminist struggle (from the Wages for Housework movement to the collective Precarias a la Deriva to feminist hackerspaces) in search of intervals, gestures, rhythms that can help us envision new forms of stoppage and ways of living together.

[1] Terranova, T. (2000) “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy,” Social Text, 18(2), pp. 33–58.

[2] Steyerl, H. (2012) The Wretched of the Screen, Sternberg Press, p. 184.

[3] Akerman, C. and G. Indiana (1983), “Getting Ready for The Golden Eighties: A Conversation with Chantal Akerman,” Artforum International, 21(10).

[4] Negri, A. (2015) “Notes on the Abstract Strike,” e-flux Journal, 65 (1).

Add new comment