Curator's Note

The forty years between Columbia Revolt (Third World Newsreel, 1968) and the anonymous footage compilation The Uprising (Peter Snowdon, 2013) was a fallow period for radical documentary. Few moving image works were produced and little academic work published on the history and theory of social change documentary. But in the 2010s, following the so-called “Arab Spring” in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, we saw an explosion of academic publication. This was not a “social media revolution,” as Western journalists insisted at the time.[1] In the decade following, however, Internet uploads produced an explosion of footage depicting state military and police street conflict with protesters. The field began to take interest in crowd-sourced websites, and the term “vernacular video” emerged.[2] If, after 2011, something has happened due to the circulation of political images, something is also happening to the theory of “the image.” What?

Now consider the 19 seconds of anonymous footage accessible on the Mosireen Collective YouTube channel from which this clip has been edited.[3] Here is amateur video from 2011, an out-of-control moment, originally “part of” a movement. From the point of view of a crowd milling in front of a line of military police, a fire hose is suddenly turned on the crowd which disperses and causes the camera to swerve upward, back and forth, at a canted angle, ending in an out-of-focus blur with a dark hooded figure frozen on the screen. Chants over the image are translated from the Arabic: “Get back. Get back” and “Down with military rule.” This video figures in debates as to what actions have been and are now “revolutionary” relative to the “Arab Spring.” Is the revolution “over” or ongoing and what does image circulation contribute to the movement?

In The Insistence of Struggle, Dork Zabunyan takes us straight to this issue. Considering the power of images of struggle continuing after the “Arab Spring” and into the Syrian conflict, he theorizes a political image function—images taken with amateur video cameras and later iPhones and circulated strategically between participants, later uploaded and re-circulated. Or, images answering images. But Zabunyan straddles a fence: On the one hand, he says these images are “visual and aural traces”; on the other hand, “they’re no longer traces but forces.” They now have, in his terms, an “operational function.” It’s the “operational function” that, at that moment, defines their “force,” that is, the way in which images are “used” by political actors. In this capacity they are “document-images” but also “force-images” originally circulated in the heat of the conflict.[4] This split between “trace” and “force” stages a new dichotomy. On the side of the “trace” is the archival document, the photographic index, representational realism, and the evidentiary logic that leads to the equation “proof = truth.” But on the other side is “force” or impact. Peter Snowdon, describing the sensory and kinetic aspects of the especially rebellious images that he compiled as The Uprising, says: “They are presentations rather than representations.”[5] Such images, said to be more concrete than abstract, may fall under the heading “operational image.” What has happened?

The editors of Image Operations posit operationality as a new research topic. What is new? Here is everything that has already been attributed to still and moving images—mimicry, resemblance, self-evidence, iconicity, potency, sensuousness, and simplification of the complex. But what is emergent are “forms of causality,” ones of “to effects of effects” and agency shifted from humans to images themselves. Images, now agents, take on “a life of their own….”[6] Here is a great blow to the representationalism in which there is reality, and then there are representations “of” that reality. But operational image theory goes much further if images are not materially different from things and events.[7] If, following theories of quantum physics, images are also matter—the same as the stuff of the world—this would mean that images are as material as fire hose water weaponized against protesters.

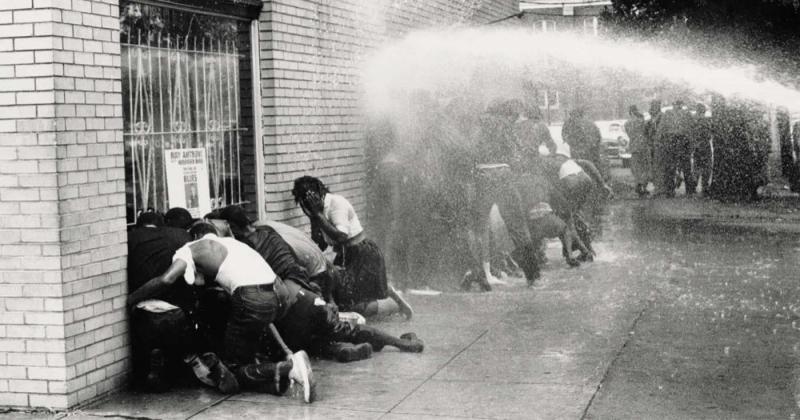

But “image operations” also emphasizes usage—not as the earlier “uses and gratifications,” with its emphasis on wants and needs, but as networked communication, images as separated, re-connected, and re-inflected. A Google search for protest images leads to historical photographs from American Civil Rights street confrontations and their classification as “hose police.” Stock footage company Almay advertises: “Find the perfect hose police black & white image.” And yet, this image is featured on the Equal Justice Initiative website:

Figure # 1. May 2, 1963. Black Children Begin Movement Protesting Segregation; Face Police Brutality.

We are pressed to rethink “images of,” to note the preposition “of” as in images are what they are “of”: “image of a fire hose turned on demonstrators.” Can the shift from what images are “of” to what it is that images do renew skepticism of “they are what they say are” given digital fakery and machine intelligence? Rethinking the indexical “guarantee” means confronting the possibility that when it comes to highly circulating images there is no guarantee—if there ever was one. In Brian Winston’s The Roots of Fake News, he still insists on the difference between verifiable “facts” and “signs of these facts” yet acknowledges the inevitable “slippage” between sign and referent.[8] Remember the post-structuralist concern about the “self-evidence of the seen” and images as “speaking for themselves.” Then also remember why cine-semiotics insisted that the sign “stood in for,” given concern that the viewer might confuse the resembling image with the represented, confuse the sign with its referent. Recall as well the worry about cinematic signifiers disappearing and representations too easily mistaken for perceptions, coupled with a concern about the behaviorism of “effects studies” premised on measuring how images “made bodies do things.” Finally, let’s not forget the related prohibition against comparing the image with the reality for which it stands, an injunction underwritten by common sense for which philosophy has its own terminology—“the correspondence theory of truth.”

Finally, we’re seeing a return to Foucault’s term “practices.” “Words and things,” as Foucault says, is an ironic title that defines a new task in which discourses are neither “groups of signs” nor “signifying elements referring to contents or representations,” but rather “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak.” Discourses, he concedes, are “composed of signs,” but beyond their basic function as signs, they do something “more.” “It is this ‘more’ that we must reveal and describe.”[9] OK, something more beyond signs. But how much more and how are we going to deal with this “more” if we think that images, in practice, may now have “a life of their own”?

[1] For some of this work, see Jane M. Gaines, “Documentary Dreams of Activism and the Arab Spring,” in Utopia and Reality: Documentary, Activism and Imagined Worlds. eds., Simon Spiegel, Andrea Reiter, and Marcy Goldberg. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2020, 238 – 258.

[2] Jon Dovey and Mandy Rose, “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online,”

in The Documentary Film Book. ed., Brian Winston. London: Palgrave/BFI, 2013, 366; For the source of the term vernacular video, see Jean Burgess and Joshua Green, YouTube. Cambridge: Polity, 2000.

[3] See Mosireen Collective: https://www.youtube.com/mosireen;

The Uprising (a film by Peter Snowdon, written & edited by Bruno Tracq & Peter Snowdon, 2013): https://vimeo.com/66820206

[4] Dork Zabunyan, The Insistence of Struggle: Images, Uprisings, and Counter-Revolutions. Trans. Stefan Tarnowski. Barcelona: IF Publications, 2019, 97.

[5] Peter Snowdon, The People Are Not An Image: Vernacular Video After the Arab Spring. London and New York: Verso, 2020, 3.

[6] Jens Eder and Charlotte Klonk, eds. “Introduction.” Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict. Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2017, 1 – 22.

[7] See Nikolaj Lübecker and Danielle Rugo, “In a Sea of Binary Algae: Marker’s Level Five as Non-Representational Documentary,” Screen 64, no. 2 (Summer 2023): 170 – 171, for a discussion of Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Half Way: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Pres, 2007.

[8] Brian Winston and Matthew Winston, The Roots of Fake News: Objecting to Objective Journalism. London: Routledge, 2021, 4.

[9] Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans. A.M. Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1972, 49.

Add new comment